Though we may not realise it most of us are faced with this question on a daily basis, or perhaps several times a day. Things happen or are said that give us unpleasant feelings. Sometimes it is about things that have not happened yet - fear, confusion or struggle about the future. Do we try to get rid of those painful thoughts and feelings or do we accept them? No one wants unhappy thoughts or negative feelings. So, we most often do what comes natural to each of us – we either try to fight off the thinking (“I must think positive thoughts!” “I have to stop thinking about this!” “God, damn it! It’s his fault I’m like this!”) or we run in the opposite direction, called avoidance – have a few glasses of wine, have another cigarette, get into another relationship, go on a holiday. While some of these things are not so “bad” in themselves, in the long term are they helpful?

Most of us have tried all types of things to deal with painful thoughts and feelings only to find that eventually they keep coming back. Many years ago I found myself reading over my daily journaling. I had kept a journal for several years since someone told me that writing down your thoughts – getting them out on paper – was the way to deal with painful or negative emotions. Well, when I do something I usually do it to the max! I had kept a trunk full of old journal books. I chanced to gaze on the 5th of April 1997. The theme of the entry was my usual struggle with relationships. I looked back one year. 5th April 1996. I was shocked. It was the same stuff. I looked back on the 5th of April 1994. Still the same stuff! Nothing had changed. I immediately felt defeated. Struggle with my thinking was a daily routine. Sounds familiar? Many of us spend a huge amount of energy, time and money in the struggle trying to eradicate or eliminate the pain.

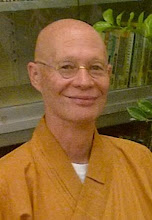

It was not until several years later I chanced to be in Shanghai, China and was introduced to a man who changed my life by changing my thinking. He has been the subject of a previous blog, the Venerable Xinming, an elderly monk from Hangzhou. He related to me how during the Cultural Revolution many monks left China for Taiwan or Hong Kong. Some stayed to resist the cultural change and paid a heavy price. Xinming told his story:

“I left the monastery, discarded my robes and went to Shanghai. Resistance is violence. The Precept tells us that we must not kill or be the cause of killing. If I resisted then I would have caused the guards to kill me and thus place them in a terrible hell. Robes do not make a monk. Temples and books do not make a monk. My life is not dependant on things but my state of mind. I was still a monk at heart. . .in my heart. I did not cease to recite the sutras silently or to “nienfo” (Buddha Name Recitation). I simply adapted. I had a purpose. This unfolded the way for me. My purpose was to live my vows no matter what and be true to myself. I was like a Chameleon. This lizard does not change being a lizard in his new environment. He simply adapts and changes his external appearance. This is the way. We must adapt.” Xinming concluded with a full heart laugh.

It took me some time to fully integrate the venerable monk’s words into my life but eventually they took root.

What does this mean to those of us who struggle with our thoughts and feelings?

Firstly acknowledge the feelings and thoughts. Realize that they are normal. They are part of what the human mind produces.

Secondly realize that you can observe them rather than getting caught up in them like watching cars pass by while standing on the side of the road instead of standing in the middle of the traffic.

Thirdly give them space. Breathe into them. Expand. Here our aim is flexibility – psychological flexibility. Breathing is very important and being present to the feelings the thoughts produce in your body. Allow them to simply be while all the time breathing into them.

Fourthly find what gives you purpose in life. What are you here for? What gives you vitality? Are you being true to your deep inner self? Continue to move in this direction as this will provide the energy.

Remember; do not get caught in the trap of trying to eradicate them. They will drag you down. The man caught in the quicksand can either struggle and sink or stop kicking about and float on the top, adapting, and perhaps having a far better chance of surviving.

This is the way of Mindfulness.